Completing the World Tour

In previous units we studied the developed nations, the so-called first world of the G-8 nations. In the last unit we expanded our study to include the BRIC’s and the many other emerging market nations, the nations that can reasonably be projected to converge on first world levels of economic development in the next generation or so.

We have, however, left some people out. Actually we’ve left out at least one billion people from our studies so far. We now turn our attention to them. These are the people and the nations of the world that live in grinding poverty, the so-called new “third world”. In polite company the current politically correct term is not “third world” but “less developed” nations. But in truth, for many of these nations the industrialization process has simply passed them by. For them, the last 40 years have seen no real development or growth at all.

We are naturally compelled to ask: Why are they poor? What can be done to change and foster development and improve the lives of these people? What needs to change? Certainly the history of several centuries has seen numerous and varied attempts by the first world (primarily Europe) to change these nations. A century ago in 1899 the English poet Rudyard Kipling penned the famous words “The White Man’s Burden”, a racist poem that exhorted European and American men to colonize and rule these nations as beneficent despots. The world and relations have changed somewhat since then. Certainly our language has changed. But before we can intelligently discuss what to do about the poverty of the bottom billion, we need to understand what forces keep them impoverished while other nations have grown. We need to understand what’s been tried in the past. And, that leads us o explore the phenomenon of “Globalization” and past relations between the developed nations and these less-developed nations.

The Change Paradox

The Change Paradox

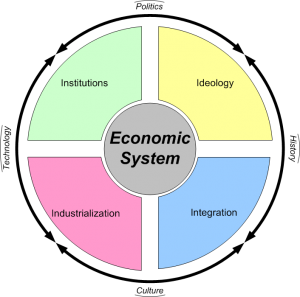

If we consult our model of economic systems as illustrated here, we are confronted with a paradox. The poor nations that make up the “third world” are those nations that require and need the most change and they need it now. They need to adopt changes in ideology, political economy and governance. They need to be integrated better into the world economy. They definitely need better institutions. And most of all, they need industrialization. Yet a paradox arises: they need the most change and there have definitely been concerted efforts to bring change in each of these aspects. Yet the overall result is the same: no change. They are just as poor as they were decades ago while the rest of the world moves on.

Who Are The Bottom Billion?

The term “bottom billion” actually comes from Paul Collier:

The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries are Failing and What Can Be Done About It is a 2007 book by Professor Paul Collier exploring the reason why impoverished countries fail to progress despite international aid and support. In the book Collier argues that there are many countries whose residents have experienced little, if any, income growth over the 1980s and 1990s. On his reckoning, there are just under 60 such economies, home to almost 1 billion people.[1]

While Collier has approximately 60 particular countries in mind, the poorest of the poor, we will try to broaden our view. In rough terms, the “bottom billion” are the one billion people in the world that live on the equivalent of $1 a day. But we don’t have to limit ourselves to that stringent measure. What we are really talking about is the large number of people who live in grinding poverty, who live a short, brutal existence, often plagued with disease or violence.

Poverty is actually a fuzzy concept. It’s difficult to measure precisely. It’s one of those “I know when I see it” concepts. The first challenge is separating out “relative poverty” vs “absolute poverty”. Relative poverty means “poorest among a selected group”. When we discuss poverty in the U.S. for example, we are often discussing relative poverty – the degree to which someone is poor relative to others in the society. For example, a family of four in the U.S. with an income of only $22,000 is defined as poor or impoverished. Clearly we are talking a different kind of poverty than what the bottom billion experience.

When discussing the bottom billion or the third world, we are talking about absolute poverty: an income that is so low that basic human survival is in jeopardy. From Wikipedia:

Absolute poverty is the absence of enough resources (such as money) to secure basic life necessities.

According to a UN declaration that resulted from the World Summit on Social Development in Copenhagen in 1995, absolute poverty is “a condition characterised by severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information. It depends not only on income but also on access to services.”[3]

David Gordon’s paper, “Indicators of Poverty & Hunger”, for the United Nations, further defines absolute poverty as the absence of any two of the following eight basic needs:[3]

- Food: Body Mass Index must be above 16.

- Safe drinking water: Water must not come from solely rivers and ponds, and must be available nearby (less than 15 minutes walk each way).

- Sanitation facilities: Toilets or latrines must be accessible in or near the home.

- Health: Treatment must be received for serious illnesses and pregnancy.

- Shelter: Homes must have fewer than four people living in each room. Floors must not be made of dirt, mud, or clay.

- Education: Everyone must attend school or otherwise learn to read.

- Information: Everyone must have access to newspapers, radios, televisions, computers, or telephones at home.

- Access to services: This item is undefined by Gordon, but normally is used to indicate the complete panoply of education, health, legal, social, and financial (credit) services.

For example, a person who lives in a home with a mud floor is considered severely deprived of shelter. A person who never attended school and cannot read is considered severely deprived of education. A person who has no newspaper, radio, television, or telephone is considered severely deprived of information. All people who meet any two of these conditions — for example, they live in homes with mud floors and cannot read — are considered to be living in absolute poverty

So how many people in the world are this poor? A lot.

So how many people in the world are this poor? A lot.

At least 80% of humanity lives on less than $10 a day.Source 1

There are approximately 6.8 billion people in the world. 80% means 5.4 billion plus. Now many of those people live in emerging market nations such as India, China, Brazil, or Indonesia. Obviously it depends upon the cut-off one uses.

What we are primarily interested in here are those countries that are not moving forward. Countries where development has not started, has stalled, or perhaps started in the past and reversed. These countries may have missed the industrialization “train” that the rest of the world is riding, but they haven’t been forgotten. In fact, these countries have long been the targets of attention from first-world governments.

Where are the “bottom billion”?

It may be difficult to precisely measure or define what “poor” is or even how it relates to standard of living. However, a graphic can often say more than simple words. Open the following link to a Gapminder.org graph (you’ll see more about how these graphs can be used in the last video in this unit): gapminder.org graph of GDP per person vs. life expectancy (link opens in new window/tab).

You will see a GDP per person on the horizontal axis. On the vertical is average life expectancy. Each nation in the world is plotted by a colored bubble. The size of the bubble represents the population of the country. Roll your mouse over each bubble to see which country it is. The giant red bubble is, of course, China. The giant light blue bubble, India. The color of each bubble represents the region of the world (see the map in the upper right corner).

Next, for an interesting demonstration of what we’ve been studying. Let’s look at how industrialization and development have lengthened lives over time. Click on the little slider at the bottom (along the time line), drag it back to 1800. Then click on the “Play” button and watch the world develop.

Notice that in 1800, the entire world is largely poor and short-lived. Then Europe, North America, Japan, and Australia break away and make for the upper right corner of rich, long lives. In the late 20th century the many emerging markets (BRIC’s and others in Asia and South America follow). But notice who is left behind: Africa. There are exceptions, Mauritius and Cape Verde are doing OK, but they are tiny African countries.